In Part 1 of my outline on Unity ahead of its IPO, I explained the scope of its multidimensional business, its R&D efforts and competitive positioning, and its grand vision for powered interactive 3D content across every industry. Part 2 digs into Unity’s financials and how it is marketing its public listing, and frames both the bear and bull cases for its future.

(This post was originally published on TechCrunch)

What are Unity’s financials?

Key financial metrics from the S-1 filing:

- Revenue grew 42% year over year from $381 million in 2018 to $542 million in 2019 with operating losses of $130 million and $150 million respectively. It hit $351 million in revenue by June 30 this year; that pace suggests a 2020 total around $700-750 million (+30% year over year).

- The company has gross margins of about 79%, although costs are overwhelmingly centered in R&D and sales & marketing which account for 47% and 32% of revenue, respectively.

- The company has cumulatively lost $569 million up to this point, including a $163 million net loss in 2019.

The geographical source of Unity’s revenue in 2019 was: 34% EMEA, 28% US, 21% APAC (ex China), 12% China, and 5% Americas (ex. US). Unlike many other Western tech companies (and game publishers), Unity operates freely in China, where it has built a large sales and professional services team over the last three years.

In Part 1, I explained each of Unity’s 7 main revenue streams. During the first half of 2020, revenue by segment broke down to:

- $216.9M (62%) from Operate Solutions (products for managing and monetizing content), the “substantial majority” of which is from the ads business.

- $101.8M (29%) from Create Solutions (products and consulting for content creation), two-thirds of which is from Unity Pro subscriptions.

- $32.7M (9%) from Strategic Partnerships & Other (Unity Asset Store and Verified Solutions Partners).

The S-1 discloses that less than 10% of overall revenue is from “newer products and services, such as Vivox and deltaDNA” (referencing key 2019 acquisitions for its Operate segment).

Some takeaways from this data:

- The largest of the 7 revenue streams must be advertising. At a minimum, 31% of Unity’s revenue is from its ads business but the amount is likely meaningfully higher than that: Unity described it as a “substantial majority” of the Operate Solutions segment revenue. Moreover, it is unclear what else is included in the company’s reference to “newer products and services, such as Vivox and deltaDNA” — in particular Multiplay, which it acquired in 2017 and is likely one of the larger revenue drivers within the Live Services portfolio alongside Vivox and deltaDNA — but that category contributed less than $54 million (10% of $542 million) in 2019. Half of Operate Solutions revenue in 2019 equates to about $146 million. That’s a $92 million gap unlikely to have been filled by the Live Services products not named. Much of it is likely attributable to the ads business.

- Unity Pro subscriptions comprise over 19% of overall revenue. That leaves under 10% of overall revenue coming from all the other Create Solutions offerings: Unity Plus and Unity Enterprise subscriptions; the engine extensions/tools like Unity Reflect, MARS, Pixyz, and AR Foundation; and consulting services. It suggests a lot of Unity’s growing portfolio of Create products still generate little revenue, especially since consulting work is a large component of Unity’s work with larger customers (as the $55M acquisition of a 200-person consulting firm in April confirms).

My estimation of Unity’s revenue composition based on the first half of 2020 is:

- 31-50% Ads (revenue-share)

- 9-20% Live services (usage-based)

- 19-25% Create subscriptions

- 4-6% Consulting

- 9% Other (Strategic Partnerships, the Asset Store, and Verified Solutions Partners)

Unity’s revenue is quite fragmented. It’s surprising Unity hasn’t translated being the most used game engine in the world, including for 53% of the top 1,000 grossing games in the $80B mobile game market, into more revenue from the core engine.

Unity adopted the freemium model in 2009 at Sequoia Capital’s urging to spur massive adoption among developers.

- On one hand, it seems the company gives too much away for free, especially since its position in the market has been the engine of the masses. Unity emphasized its enterprise focus in its S-1, sharing that 74% of overall revenue comes from 716 companies paying Unity over $100,000 annually (versus over 100,000 customers below the $100,000 per year spend level). That its revenue comes overwhelmingly from companies with large budgets (who can then also afford highly skilled developers) is somewhat disconnected from its traditional market position: outside of mobile games, that’s the territory in the market where Unreal tends to win more.

- On the other hand, perhaps optimizing for wider market adoption will continue to create upward pressure on large companies as well. Many companies do choose Unity because there’s a larger talent pool who know how to use it. As non-gaming companies adopt game engines they will find it easier to hire Unity developers.

Why isn’t Unity profitable and what will it take to get there?

Unity’s lack of profitability appears to stem from its enormous investment into expansion. R&D accounts for 47% of revenue, Sales and Marketing for 32% of revenue. Per his own words in one of our past interviews, John Riccitiello expanded the engineering headcount from about 100 when he took over in 2014 to over 1,500 by 2019.

Unity’s expansion into other gaming infrastructure offerings and its expansion into other industries are both in early innings in terms of their revenue impact and market penetration. It will require substantial ongoing R&D and Sales & Marketing investment to fuel growth in those two areas in line with Unity’s stated ambitions. This suggests several more years of operating losses until Unity’s Live Services portfolio and its expansion beyond gaming each gain much greater market penetration.

What to watch for in Unity’s IPO

Unity will hope for investors to value it as a high-growth SaaS company; such companies were hitting valuations earlier this year in the 15 to 30 times revenue range and that jumped over the summer to 20 to 40 times revenue in some cases. It also will want to benefit from comparisons to Epic Games, given it was just valued at $17 billion and has much greater public name recognition and hype.

To accomplish this, Unity seems to be underplaying the significance of its advertising business (adtech companies trade at much lower revenue multiples). In the past, Unity referred to its operations in three divisions: Create, Operate, and Monetize. At the start of August, the SVP and VP leading the Monetize business switched titles to SVP and VP of Operate Solutions, respectively, and then Unity reported the Monetization business as a subset of its Operate division in the S-1. Consolidating Operate and Monetize into one reporting segment obscures specifics about how much revenue the ads business and the live services portfolio each contribute. As noted above, this segment appears to be dominated by ad revenue which means anywhere from 30% to 50% of Unity’s overall revenue is from ads. That should reduce the revenue multiple public investors are willing to value Unity at relative to recent and upcoming SaaS IPOs.

There isn’t a publicly-traded game engine company to directly benchmark Unity against, nor a roster of equity research analysts at big banks who have expertise in gaming infrastructure. Adobe and Autodesk appear to be relevant businesses to benchmark Unity against with regard to the nature of the non-advertising components of the business and Unity’s stated vision. Compared to Unity, those companies have lower growth rates and generate operating profits though; more recent public listings of SaaS companies like Zscaler and Cloudflare are likely to be valuation comps by investors to the extent they focus on its subscription and usage-based revenue streams since their revenue growth and margins are closer to Unity’s.

Unity’s market penetration holds a lot of strategic value in the gaming and AR/VR markets that may add a premium to its value. Any attempt by one major tech company to acquire Unity would almost certainly cause a bidding war with others. When Facebook hoped to acquire Unity back in 2015, Mark Zuckerberg wrote that the risk of Unity falling into the hands of a competitor “is such a vulnerability that it is likely worth the cost just to mitigate this risk.”

What is the bear case for Unity?

A pessimistic view of Unity is that it’s an advertising-centered business pouring itself into finding new growth in other markets but unable to show substantial ROI yet on those investments in expansion. And it faces better-resourced competitors at every turn.

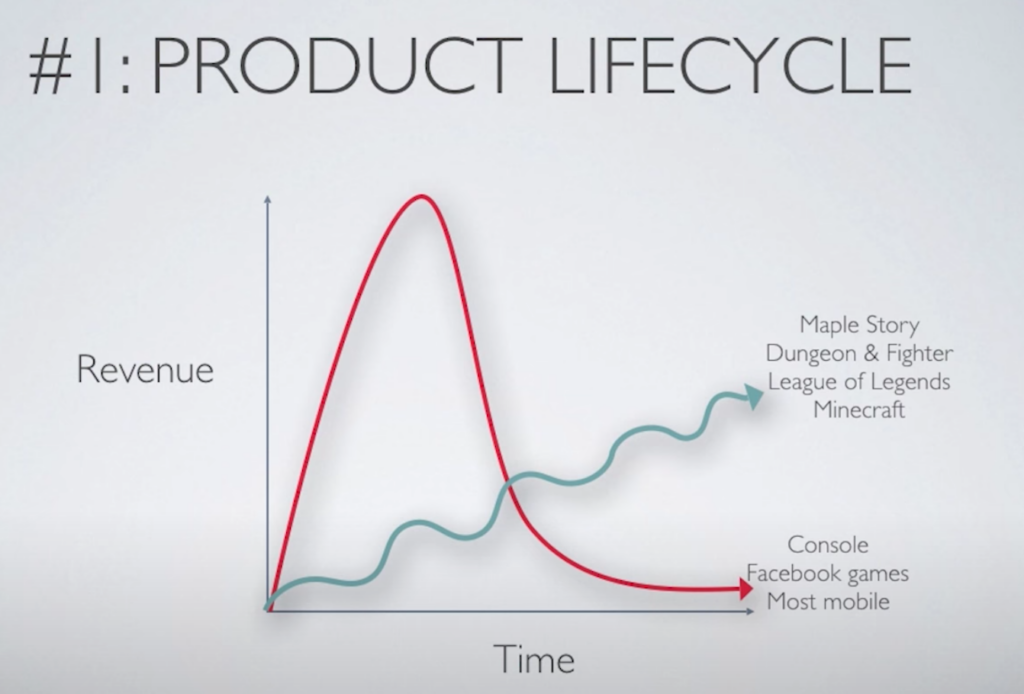

Unity has nearly saturated the mobile gaming market, limiting future growth for the engine. It is getting ever tougher for small mobile studios to break through the noise and the advantages of incumbents, and top game companies nowadays are focused on expanding their existing hit games rather than launching a lot of new ones. Since successful studios pay Unity on a flat per-seat basis not a revenue-share basis, Unity’s engine revenue doesn’t benefit from more concentrated ownership of the top mobile games.

Despite Unity’s massive popularity, it makes little to no money off the mid- and long-tail of game developers it is most popular with, given 74% of revenue is tied to the 716 largest customers and two-thirds of all Create Solutions revenue comes from Unity Pro tier subscriptions.

Moreover, gaming’s future will feature greater dominance by a handful of cross-platform MMOs where people build social lives and participate in non-gaming activities like virtual concerts and trading of digital goods in addition to core game play. That’s a use case Unity’s main competitor, Unreal, is specifically built for.

Unity’s fragmented revenue streams suggest it has been grasping for better ways to make money off the widespread adoption of its product and struggling to come up with a clear solution. Its revenue comes from a little bit of everything rather than one, massively successful strategy.

The dominant revenue stream is advertising solutions, which aren’t valued at high revenue multiples by public market investors because it’s a crowded market and hard to differentiate. While Unity Ads is one of the largest mobile ad networks in the world it is still far behind Google and Facebook’s. In-game ads is a $3 billion market according to Criteo (a very small subset of the overall mobile ads market) and most categories of advertisers don’t participate in it.

Moreover, Apple’s forthcoming changes to IDFA — now delayed until Q1 2021 — are causing major upheaval in the mobile ads market due to the dramatically more limited ability to target ads. Unity’s ad revenue could be hurt by this is, as noted in the Risks section of the S-1. Apps will only be able to track user behavior across their phone in order to target ads if the user specifically opts in, which few will do. Apple’s SKAdNetwork will be the only way to receive data on users’ behavior beyond the app and it will be much more limited data. This will make it difficult to target in-game ads and to measure the effectiveness of in-game ads at converting new customers.

While Unity only provides advertisers with behavioral data of users’ actions within a game, advertisers use the user’s unique identifier to match them with information about them gathered from other sources. Advertisers may pull back from spending on mobile ads overall, including within games. When Facebook tested the removal of personalization features from mobile ad install campaigns in its ad network in June, it saw a 50% decline in publisher revenue. Since Unity earns money through a revenue share with publishers using its ad network, a major decline in their ad revenue would proportionally decline Unity’s ad revenue.

Unity is staking its vision for growth on expansion to other industries and expansion to other types of gaming infrastructure but both of those expansions are still nascent in terms of their revenue impact.

Unity’s expansion into other cloud-based game infrastructure products appears to only account for 9-20% of revenue, most of which is inorganic growth through recent acquisition of startups. There isn’t dramatic advantage to game studios from the vertical integration of tools for matchmaking, game hosting, and player communications with the engine they use; each of these products will continue to face competition from other startups and large companies and any move by Unity to force engine customers to use only its Live Services products would diminish its popularity as an engine. The more Unity grows in cloud hosting and gaming infrastructure, the more direct competition it is likely to face from tech giants like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon as they each expand both their cloud and gaming businesses.

Unity claims there is currently a $17 billion TAM for use of their products beyond gaming, with 37 million engineers and technicians who could be using these tools. But the expansion of Unity’s engine into other industries shows little revenue impact thus far despite being a central focus of the substantial investment in R&D and sales & marketing over five years: just 60, or 8%, of the 716 customers who contribute over $100,000 in annual revenue are from outside gaming.

This expansion faces direct competition from Epic, which has a much larger war chest due to profits from its game development business, but it’s not clear yet whether non-gaming industries offer huge growth opportunities for either of them. If you call professionals in the industrial sectors these engines are targeting, the typical response is that more people are becoming aware of them and experimenting with them but they are not taking the industry by storm. In these segments, Unity’s business is a hybrid of a consultancy and a startup whose software is being used in a lot of promising pilots and an initial group of customers but hasn’t definitively established itself in the market.

Public market investors will be taking on a lot of risk that growth will come from unproven new markets compared to typical NYSE IPOs.

What is the bull case for Unity?

An optimistic view of Unity is that it is positioned to become one of the most important technology companies of the decade ahead as gaming (and socializing within virtual worlds) continues to explode in popularity and as 3D interactive media takes center stage in our personal and professional lives.

The Unity engine is the most popular content creation platform in a massive, fast-growing market. There’s still solid growth in the upper echelons of the mobile games market where studios pay more for Unity. According to App Annie data, 1,121 gaming apps generated at least $5 million in revenue in 2019, up from 1,055 in 2018 and 959 in 2017; at the top of the market, 140 games generated over $100 million in revenue last year, up from 116 in 2018 and 88 in 2017. Unity is used for 53% of the top 1,000 mobile games and has more growth opportunity both in terms of market share and absolute number of large mobile game studios.

The company has an impressive ability to upsell existing customers to add additional products and services — with a 142% net expansion rate on 12-months trailing revenue as of the end of June. That represents substantial untapped potential within mobile games for its growing portfolio of Live Services products. Since the focus of successful game studios is increasingly on expanding existing hit games, there is increased demand for tools to support such “live ops” work and urgency to regularly update the game with new content. Unity’s Live Services portfolio offers those tools as third-party solutions so the studio can keep its staff focused on new content creation.

Unity’s mobile game monetization products still have a lot of growth amid the surging overall mobile ads market ($200 billion with a 14.3% CAGR per Statista). Unity targets ads based on contextual behavior of users’ gameplay so Apple’s IDFA changes will have more limited impact than on other ad networks. The dominant advertisers in mobile games are other mobile games — for them gaming behavior is the most effective personalization data. The insularity of in-game ads by other gaming companies cushions Unity ad revenue from broader ad market shifts (as seen this past March and April as the economic recession hit and mobile games ad revenue increased 59%). It also suggests how much potential growth there is as advertisers in other categories recognize mobile games as an environment in which all demographics of consumers are highly engaged.

Importantly, Unity doesn’t yet take a revenue-share for optimizing in-app purchases (IAP), but it could. That’s a huge growth opportunity since consumer spending on mobile games is a $77 billion market, growing 13% year over year, according to Newzoo. Mobile game industry revenue is heavily concentrated among the most popular games, the majority of which are made with Unity. Unity could create a multi-billion dollar business in the years ahead just by improving IAP solutions for mobile games and charging with a revenue-share.

Unity has made enormous strides in catching up to the customization and technical feats of the Unreal Engine as it expands beyond mobile games, in particular with its data-oriented tech stack (explained in Part 1). Critiques of Unity’s lesser capabilities stem from old norms that it has since surpassed. For most games and non-gaming use cases, Unity is fully capable of achieving the level of customization and performance needed.

Unity’s popularity is a highly defensible moat itself. It is the engine most students and professionals use to build interactive 3D content. As a result, it is preferred by companies because of the large talent pool to recruit from and there are a lot of young professionals trained in Unity who will see applications for it at non-gaming companies they work at.

Game engines are eating the world, as outlined in Part 1. A vast swath of entertainment and work activities already center on interactive content. Unity has demonstrated value and early adoption across numerous industries for a long list of use cases; it is on the precipice of entering the daily workload of millions of professionals, from engineers to industrial designers to film producers to marketers. Its Create Solutions division is on a path to becoming something of a next generation Adobe ($11 billion in 2019 revenue): a creative suite used by design, engineering, marketing, and sales teams across industries.

As AR and VR technology expands into mainstream use over the decade ahead, Unity’s adoption will only expand further. The majority of AR and VR content is already made with Unity’s engine and Unity’s R&D is improving the ease of creating such content by less technical professionals (and students). This positions Unity to expand into key functions higher up in the tech/content stack of mixed reality by providing identity, app distribution, payment, and other solutions across content experiences.

Unity has only one other core competitor as a game engine expanding into these industries, and in the scope of the dramatic market size and different product design philosophies there is room for both to co-exist. The biggest barrier to growth is educating the market on what game engines are and how they can be used; Epic’s investment in growing Unreal does more to help this effort than to hurt Unity.

Unity’s rise has been a consistent story of staying ahead of the curve, building content creation solutions for new formats of content as they gain popularity. It is simultaneously becoming more powerful of a platform and easier to use, a combination that allows it to compete at the top of the market while expanding the overall market to more users.