Read my post on TechCrunch: https://techcrunch.com/2018/10/17/why-igtv-should-go-premium/

Category: Monetization

What Spotify can learn from Tencent Music

Read my post on TechCrunch: https://techcrunch.com/2018/10/05/what-spotify-can-learn-from-tencent-music/

MoviePass, AMC, and the Era of Cinema Subscriptions

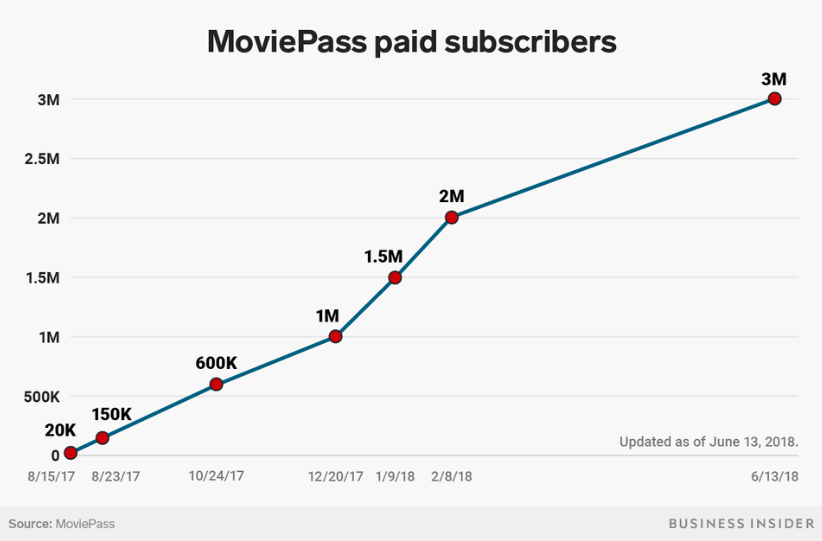

AMC Entertainment announced a $19.95/month subscription last month called the AMC Stubs A-List for movie-goers to see up to 3 movies per week at its theaters (Stubs is their rewards program). This is a big experiment for AMC – the largest exhibitor chain (aka cinema chain) in the world – not least because its CEO Adam Aron has been very critical of MoviePass, which set off a rush of interest in subscription cinema packages after dropping its price from $50/mo to $10/mo last August and growing from 20,000 to over 3M subscribers since.

MoviePass is on a mission to “disrupt” the film industry with an all-you-can-watch membership so cheap it’s a no-brainer for any person to join. The company has negative unit economics (it loses money even from a subscriber going to one film per month) but says it will generate other revenue streams like advertising, selling data to film studios, producing its own films, and convincing exhibitor chains to give it a cut of food & drink revenue (Aron has said AMC would never agree to that).

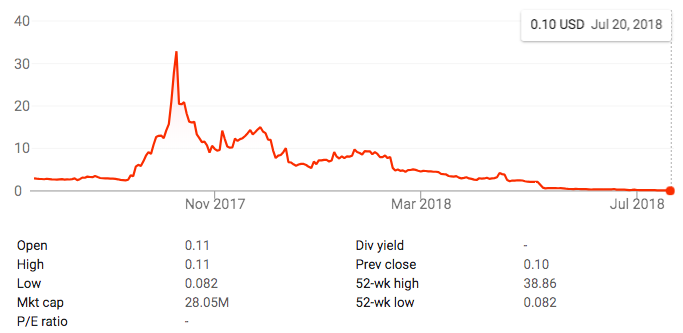

The growth rates of MoviePass led the Nasdaq-traded shares of its holding company, Helios & Matheson Analytics, to increase from $3 a year ago to $38 by October 2017, but the ever-deepening losses have caught up: its shares are currently trading at $0.10 ($26M market cap). Not phased, Helios & Matheson CEO Ted Farnsworth claims they’ll raise another $1.2B in equity and debt financing over the next couple years to expand an in-house film production arm and will be cashflow positive by the end of 2018 (assuming they reach 5M subscribers).

The growth rates of MoviePass led the Nasdaq-traded shares of its holding company, Helios & Matheson Analytics, to increase from $3 a year ago to $38 by October 2017, but the ever-deepening losses have caught up: its shares are currently trading at $0.10 ($26M market cap). Not phased, Helios & Matheson CEO Ted Farnsworth claims they’ll raise another $1.2B in equity and debt financing over the next couple years to expand an in-house film production arm and will be cashflow positive by the end of 2018 (assuming they reach 5M subscribers).

Does a subscription for movie tickets make sense?

A subscription often makes sense when you have a recurring purchase frequency (of roughly the same price point) and when you can offer customers extra benefits for their loyalty that they can’t already get from one-off transactions (like cost savings, improved experience, sense of membership in a community, etc.). The upside for a business is the low cost to acquire a customer (CAC) relative to their lifetime value (LTV) since they keep paying without you having to target them with marketing campaigns every time; predictable financials from a regular payment cycle; and deeper customer engagement (often more spending and more data collected).

We’re several years into “the subscription economy” where it seems companies are testing the idea of a subscription for every product and service consumers use: clothing, cleaning products, wine, dinners, flights, meditation, music, video, books, doctor visits, etc. Nearly every media company seems to be launching a subscription video-on-demand service or subscription membership tier to read articles. Consumers are used to subscriptions for all sorts of things now, and there’s opportunity to bundle them together for joint promotions that acquire new customers (like Spotify x Hulu for $12.99).

To set the context for a movie tickets subscription, let’s consider some stats on the state of movie-going in the US & Canada [1]:

- Three-quarters (76%) of the population over 2 years old went to the movies at least once in 2017 and people who go to the movies tend to go 5 times per year on average. More specifically, 12% of the population goes once per monthly or more, 53% go less than monthly but multiple times per year, 11% go once per year, and 24% go never.

- Half (49%) of ticket revenue comes from those who go monthly or more and most of those (57%) are in the 12-38 year old age range.

- Roughly half of exhibitor chains’ revenue comes from concessions, but concessions have much higher profit margins, so a disproportionate amount of the profit comes from customer spending once they’re in the door.

- Total box office tickets sold was 1.57B in 2002, and has declined in recent years to 1.24B in 2017 (the lowest since 1992). But the sales of those 1.24B tickets amounted to an $11.1B market (the 3rd highest ever after 2016 and 2015). That’s also twice the attendance of theme parks and pro sports events combined.

- Exhibitor chains are increasing ticket prices (2017 avg: $8.97) and concessions prices to make up for the fewer customers and are investing in making the cinema a “premium” experience with leather recliners, high-end food service, alcohol served in-theater, etc. They need to extract more money from the cinephiles who are frequent movie-goers.

A monthly subscription, even at a good price, won’t convert consumers who never go to the cinema or go merely once a year. It could entice a swath of the people who attend movies several times a year to increase their attendance to roughly monthly though…the subscription offers them enough savings and perks when they do go that they decide to try it out, then opt to go to the movies more because they have it (or opt not to cancel it even if they miss a month or two).

Of course, a monthly cinema subscription is most compelling to 2 groups who might see immediate savings: those who already go once per month and those who already go multiple times per month. Monthly attendees already have a habit of going to the cinema as a common activity, so a subscription that gets them in a second time for free will increase the frequency for many of them to above 1x per month (spending more on concessions if not on tickets).

Cinephiles going multiple times to month to the cinema will jump both to save money and to get special perks via a subscription. Of course, these people are the most profitable for AMC and others – already buying lots of tickets and concessions – so dramatically reducing how much they’re paying for tickets could be detrimental to the business.

This is why tiered subscription models make sense if this business model is going to be sustainable. Often when a consumer subscription model is implemented, it starts with just one tier to keep it simple, then adds other tiers over time to capture (and provide) more value to different customer segments. MoviePass and AMC have one-size-fits-all subscriptions at the moment, but the market lends itself to at least a two tiers. The base tier should be a price that entices people to go once or twice a month. This is about expanding the market of monthly customers with a no-brainer price (like <$10/month for 2 tickets) that triggers rapid scale, converting a meaningful percent of those who only go to the movies a few times per year. Perhaps it has restrictions on being used for peak times (i.e. opening night of a Marvel movie) or for IMAX.

The second tier should be for cinephiles; they are fine spending $30+/month at the cinema already, and what they crave is likely special perks and community more than deep discounts on tickets…which is the smart move for the exhibitor too. The goal here is to deepen their engagement further, come up with new offerings for them to spend on, and mobilize them as evangelists. This tier should provide a percentage discount on the third and subsequent tickets per month or be a higher-priced all-you-can-watch offering, include peak times and IMAX movies, have extra concessions and viewing perks, give first dibs on opening night tickets, include online or offline film discussion groups, incentivize bringing friends, etc.

The problem with MoviePass

Let’s consider MoviePass as a marketplace: it has consumers on one side and cinemas on the other, with the consumers choosing which cinemas they want to buy tickets from. Startup marketplaces gain adoption and powerful market position by aggregating consumer demand on one side and sellers (or service providers) on the other. The model thrives in fragmented markets with lots of small- and mid-size companies competing with each other. Because the startup has aggregated lots of consumers on one side, the companies have to participate or risk those customers being directed to competitors. That’s the power marketplaces have over the supply side and exploit to compress supplier margins over time (passing savings on to the consumer while pocketing some as the middleman). MoviePass is aggregating consumer demand through a money-losing ticket subscription then hoping to leverage that to force exhibitors into cutting them into concessions revenue, giving them discounts on tickets, etc. Potentially it will split its offering into multiple tiers, although management has said they’ve no intentions to do that even in the long-term.

The problem here is MoviePass doesn’t actually gain much leverage over exhibitors because this is a fairly concentrated market. There are few mom-and-pop cinemas left in North America (especially few showing major Hollywood films rather than indies). Three companies – AMC Entertainment (owned by China’s Dalian Wanda), Regal (owned by the UK’s Cineworld), and Cinemark – have 50% market share in the US cinema landscape and they’re taking it over more each year (plus they’ve even greater dominance in major metro areas) [2]. In Canada, one chain – Cineplex – owns 78% market share [3]. Each individual consumer only has a tiny number of cinemas that are a convenient travel distance to them that show the major films…and it is probably some combination of AMC, Regal, and Cinemark (or just Cineplex). If a consumer decides they want to go to the movies, they’re most likely going to one of those regardless – MoviePass doesn’t have much power to steer them elsewhere. Movie-going is an offline experience, so having tons of smaller chains around the country collaborating with MoviePass is irrelevant to any given consumer; the only ones that matter are the few cinemas closest to them.

The major exhibitors can provide their own subscriptions that offer more perks to members since they own the show (i.e. they’re vertically integrated): AMC offers 10% off concessions, upgrade to the largest popcorn/drink size, and priority lines for seating and concessions. They can also capture additional offline data on moviegoers like what they’re buying at concessions, who they’re attending with, their mood and appearance (using computer vision), etc. and use all the customer data to improve the in-person experience (ushers welcoming you by name, ordering your usual food/drink in advance with one tap, etc.). Plus, by owning both the online and offline customer interaction, the exhibitors then have the data to sell better targeted advertising that can bridge the online and offline experience.

What will happen to MoviePass?

Ultimately, MoviePass is lacking the financial footing for large lenders or equity investors to back it with the war chest of capital its grand plan would really require. I think MoviePass will continue to burn cash and ultimately get acquired by a major exhibitor (AMC, Cineworld, Cinemark) or SVOD player (Amazon, Netflix) who can make immediate use of its subscriber base and user data.

Unlike most startups where the majority shareholder or board have to compete say over whether to take a deal, MoviePass’ holding co is publicly traded. So if an acquisition offer comes in that is strong based on where the stock has been trading for a while, the company’s leadership opens itself up to shareholder lawsuits if it doesn’t seriously consider it (and have a good reason for turning it down).

This is just the beginning.

The subscription offerings by AMC and other top exhibitor chains can be compelling for all parties if priced and tiered intelligently, and they’ll accelerate further consolidation in the exhibitor market (like SVOD services have triggered in film/TV) because each will want its subscription to contain the popular cinemas in any given city. Consumers will naturally only have one cinema subscription each, so securing their long-term loyalty with one major chain over its rivals will be big a high priority to the exhibitors.

Furthermore, these subscriptions will expand beyond just movie tickets to other offline entertainment offerings. That’s the direction exhibitor chains are already moving in the face of a secular decline in cinema attendance…forward-thinking exhibitor chains are re-envisioning themselves not as movie-watching companies but as what-you-do-on-weekend-nights-with-friends companies. Several chains are incorporating Virtual Reality arcades, others are using some of their theaters for esports tournaments, some have TVOD movie rental if you decide to stay at home, etc. (Cineplex is doing all that and more). By expanding the membership to include activities beyond just movie theaters, they can attract many more of those who only go to the movies a few times per year to sign up. The grand opportunity here, in my opinion, is to create the Amazon Prime membership of offline entertainment experiences…a cost-saving bundle across a wide range of activities that becomes a no-brainer for a large percent of the adult population to enroll in. That’s the direction I expect this is all going in.

Sources:

[1] MPAA THEME report 2017

[2] US market share by screens, from this NYT article

[3] Cineplex market share in Canada from their investor relations

SVOD and Protectionism

The Dutch Culture Council recently asked legislators to require SVOD services operating in the country to maintain libraries with at least 15% Dutch content and apply a 2-5% tax on all revenue derived from foreign content streamed in the country. It’s a protectionist move both to nurture the Dutch film/TV industry in a competitive global market and to protect Dutch culture from the overwhelming pop culture influence of Hollywood. It’s also increasingly common around the world.

Local content quotas have long existed in television. Now that governments are wrapping their head around online streaming – and especially amid the surge of nationalist populism – clampdowns are coming.

The EU Parliament voted last year on a mandate that 30% of content on VOD platforms be European (FYI: Netflix’s library in Europe is already ~20% European). National governments are layering national quotas over that. Italy raised its local content quota on TV (which is supposed to include SVOD) to 60%. France already has a 60% quota on TV and is pressuring VOD platforms to substantially increase quotas as well, with Netflix CEO Reed Hastings committing to increase the company’s French content production by 40% in 2018.

In China, 70% of content on SVODs must be Chinese (hence why Netflix doesn’t operate there and instead signed a distribution deal with Baidu-owned iQiyi).

The net effect is a limitation on the amount of international content made available to subscribers in these countries and an increase in local content that doesn’t meet the bar for quality those platforms otherwise require. But the concerns are legitimate. The dynamic of online streaming platforms is a hits business. As Netflix and Amazon Prime Video expand globally, their hit shows become the hit shows across every geography. And the resources these SVOD platforms have to invest in their own content dwarfs that of local studios; even Rupert Murdoch felt 21st Century Fox wasn’t big enough to compete on its own. Local content quotas (and potentially streaming taxes) help nurture the local media industry to produce local hits (and sometimes global hits), which is important economically and culturally.

I wonder, however, how feasible content quotas are outside censorship-heavy states like China. How do you define regulated streaming content vs. content that’s just part of the broader internet (like Youtube videos)? What about SVOD services whose entire niche is to share a certain culture’s content with people abroad, like BritBox – a 250,000-subscriber service entirely dedicated to British TV shows and classic British films? If they’re restricted enough, won’t Europeans just use VPNs to access content that Netflix subscribers get in the US?

(This post is an abstract from today’s MediaDeals newsletter.)

Why People Aren’t Paying for Your Content

Reliance on advertising is often a way to mask the fact that a media property hasn’t found “product-market fit”.

To find success in any market, you need to offer a product that’s 1) compelling and 2) differentiated. A compelling product adds value to the consumer: it offers a functional benefit and/or emotional stimulation that they place value on. A differentiated product is something they can’t get elsewhere…the brand, the technology, the affordable price point, the geographic focus, or whatever else is fairly unique.

A product that’s differentiated but not compelling is just something no one wants – there’s no market for it. Alternatively, a product that’s compelling but not differentiated has no wedge to break into a market and no sustainable business. You have a commodity product so consumers will just go with whoever offers the same thing for cheapest or who they’ve already been buying from.

Entrepreneurs know they have a product that’s both compelling and differentiated when they receive consistent enthusiasm from customers willing to pay a sustainable price. So when an entrepreneur puts a product out and few people are willing to pay for it, it sends them back to the drawing board. They iterate until they finally find “product-market fit” or run out of money and stop.

In media, there’s a common opt-out here. Media entrepreneurs will produce content that’s compelling but not differentiated; there’s an audience but they’re not willing to pay for it. Rather than iterating to find product-market fit, they sing the common – but false – refrain that “people won’t pay for content anymore” and turn to advertising as a way to monetize the initial audience. It’s the fallback option. But in doing so they’ve moved out of media and into the advertising business…the attention business, the quantity-over-quality business. The content they produce gradually reflects this goal (see The Problem with Advertising). The problem is worst in news publishing, where – since the internet has removed mere geographic location as a differentiator – most publishers produce the same news stories without unique voice or analysis.

The reality is that if people won’t pay for your content it is, simply enough, because they don’t think it’s worth paying for. It doesn’t mean the content isn’t compelling, it might just not be differentiated from what can easily be found elsewhere. In the media industry, there’s not enough pressure to confront this reality and find product-market fit because advertising offers a short-term escape route.

Business Models for Media Companies

How do media companies make money? Across media formats (writing, videos, music, podcast, games, etc), there are 5 overarching business models to generate revenue from the content your company creates: 1) transactions, 2) subscriptions, 3) licensing, 4) content marketing, and 5) advertising. Let’s review.

1. Transactions

Transactional business models are the simplest way to make money off content: slap a price tag on whatever you create and charge for it…just like you would when selling a pair of shoes. This works best when you have larger, clearly defined pieces of content that people are likely to want as one-time purchases separate from other content you have created. We are talking about books, films, albums, games, online courses, research reports, etc.

Transactions can be for content to own or for content to get temporary access to. In the former, the customer buys a copy of the content that they can download or walk away with (i.e. they own a copy forever); in the latter, the customer buys access to content that remains hosted on the distributor’s platform so they can end access after a period of time.

Buy to Own/Download to Own

Historically (pre-Internet), people have bought physical copies of content: a book from Barnes & Noble, a record album from Virgin Megastore, a DVD from Best Buy, a video game from GameStop, etc. As content consumption moved online, this type of transaction went with it: in iTunes, you buy content, download it, and can send the file around to other devices. In a business context, you might buy a report from a market research firm and receive it as a PDF to download. Buying to own is still widespread online.

Pay-to-Unlock

The alternative – and the increasingly common model – is to buy temporary access to content that remains hosted elsewhere so you can’t take a copy to do whatever you want with. For example, a pay-per-view boxing match that costs $100 to see on TV or a movie available for 48-hour rental on Youtube at a price of $2.99. Renting individual movies or TV shows to watch online is referred to as TVOD (Transactional Video-On-Demand). The period of time you get access to content for could be indefinite, but without having a copy of the file itself, you don’t own the content.

From a media company perspective, the pay-to-unlock approach reduces the threat of piracy, which is common with download-to-own content since consumers can send the file to friends or upload it for free on another site. Moreover, a media company collects tons of data about how people are interacting with content they’re hosting; they don’t get data from people interacting with downloaded files.

A newer innovation is pay-as-you-go content consumption through micro-transactions. The Dutch startup Blendle, for example, created a platform for reading articles from a wide range of publishers that charges you a few cents per article you read. Each piece of content is a new transaction, but because you have pre-loaded your Blendle account, you don’t have to go through a new payment process every time. There are many efforts to use blockchain technology to do micro-transactions on an even smaller scale (i.e. less than $0.01 per article) as well. This micro-transactions model hasn’t taken off in a big way though.

In-experience purchases

In video games and some other interactive forms of media (like VR and AR experiences), you can charge your users money to access tools or other benefits within the experience. Like in a video game, players can spend money to buy a more powerful fighting sword or get more virtual coins. These in-app purchases (IAP) or in-game purchases have become the core of the games industry. The release of the iPhone in 2007 created a boom in mobile games, who found that they make the most money by being free to play (F2P) and then incentivizing players to spend money on optional purchases within the game.

2. Subscriptions

In media, subscriptions are based on access to content for a period of time that’s recurring (typically monthly cycles). It locks in an ongoing relationship with the customer, who has to opt-out of the recurring payments if they want to stop being a customer. Usually, the subscriber gets access to a pool of content that they can consume at will, rather than only getting access to one piece of content.

Because subscribers continue to pay on an ongoing basis, they also expect new value to be provided on an ongoing basis. You typically don’t pay a subscription to consume the same unchanging piece(s) of content again and again; you pay a subscription for ongoing access to a flow of content that’s regularly refreshed with something new. That could be daily news articles, monthly refreshing of movies on Netflix, etc.

Newspapers and magazines tend to operate on subscriptions because they are comprised of many small articles people consume a high volume of. Similarly, SVOD (Subscription Video-On-Demand) platforms – like Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu, VRV, fuboTV, etc. – have gained traction because people watch enough content on them that they prefer an all-you-can-watch subscription rather than having to consider each film or TV episode as a new purchase.

Because the relationship with a subscription customer is not tied to one specific piece of content but rather the broader offering available to them, the value they measure is their overall experience…the quality of content they’ve consumed, the affinity they feel for the media company’s brand, the “fear of missing out” if they unsubscribed. In this dynamic, subscribers are like members of a club…winning and retaining their business is about a relationship rather than a one-time transaction. It also means that you’ve locked in recurring revenue just by gaining one new subscriber; in a transactional model, you have to fight for every purchase you want a potential customer to make, regardless of whether they’ve shopped with you before (i.e. you have a new “Customer Acquisition Cost” or CAC for every sale).

(Subscriptions don’t have to be only for exclusive content. Sometimes there are other benefits that the audience is willing to pay a subscription for; for example, in mobile games there are often subscriptions that remove annoying ads so you are aren’t interrupted by ads while playing.)

3. Licensing

Many creatives want to stay out of the direct-to-consumer business…they just want to create the content they want, then license the rights to another media company that handles marketing and distribution. This is the classic way Hollywood and other creative industries operated; pre-Internet, it was incredibly difficult for creative teams to also distribute their content. Much of that traditional infrastructure is still in place. There are lots of structures for licensing; sometimes it’s one upfront payment, sometimes there’s a revenue share on the sales (aka royalties).

Films follow this path: a production company sells the film to a studio that markets it and negotiates with exhibitors (i.e. cinemas) and online streaming platforms to distribute it. Television shows are created by production companies, bought by networks, and distributed through networks’ partnerships with cable companies. Music, books, and games are more direct-to-consumer nowadays than they once were, but the traditional distributors still remain important (i.e. record labels and streaming platforms; publishing houses and e-book platforms; game publishers).

This route makes sense when you work on a small number of big productions, each of which might be unrelated to the others in terms of theme, target audience, etc. It would be inefficient to launch every new film as its own standalone media company that has to build an audience from scratch, for example.

The downside of licensing is that the fate of your content is dependent on middlemen, and you collect little-to-no data on who your audience is and how they’re consuming your content. Without that data and without direct interaction (getting their email addresses, etc.), it is tougher to build ongoing relationships with fans and engage them with new offerings.

4. Content Marketing

Content marketing is, simply put, using content as a tool to market some other product or service from which you make money. (Content marketing is also done by individuals to market their personal brand, with the ROI coming from the benefits the notability brings to their career.)

Brands using media as marketing

Content marketing has exploded in recent years within the marketing departments of companies across every industry. Companies that are bad at it plug their product offerings extensively so there’s no mistake you’re reading/watching promotional material; companies that excel at it focus on creating high-quality, engaging content that develops a relationship between their brand and the audience like a media brand would.

Airbnb, VC firm Andreessen Horowitz, Coinbase, Hubspot, United Airlines, and tons of other non-media companies have launched media products that operate as a loss because of their marketing value to the rest of the business. Some media entrepeneurs decide to launch their brand as part of a big company’s marketing department (or sell it to them, as we saw with Hubspot’s acquisition of The Hustle).

The content marketing model can also start with media, then expand into relevant products/services to sell once you’ve crafted a brand and audience. In fact, many free-to-read news outlets in the business world are – when you look at their business model – live events companies with extensive content marketing. They cover industry news through articles and videos, and they do monetize that through advertising, but the largest revenue generator is the conferences they host, which are marketed to their business audience with ticket prices ranging anywhere from $500 to $5,000 plus sponsors paying to reach those attendees.

Media companies with e-commerce

A common content marketing model for independent media properties is using IP from the content to do e-commerce…selling merchandise for passionate members of your audience to purchase, just like bands do with their fans. Sites ranging from WaitButWhy to BuzzFeed have done this. Publications like the Wall Street Journal have curated products from other companies to sell in an e-commerce section to their audience. There’s a grey area between being a media company and a consumer brand nowadays.

Affiliate linking

Affiliate linking is when a media site puts links to other companies’ products in their content and gets paid a fee for referring the traffic. This has become a big part of the digital publishing industry. Sites with write product reviews, travel tips, cooking recipes, etc. and link to sites where you can buy the products they mention. They often frame themselves as neutral reviewers but their business model is to drive sales of the products they link to.

Anyone can earn affiliate income from linking to Amazon products since they have a standardized referral program. In other cases, the media company negotiates their own deal with the product sellers. Sometimes the media company is paid based on the amount of people who click the link (pay per click), other times they are paid a flat fee or a percentage commission of that people they refer end up spending.

The New York Times’ Wirecutter is a major player in the product reviews category. Red Ventures’ The Points Guy is a dominant media site for referring Americans to sign up for credit cards with travel rewards. There are thousands upon thousands of sites making money this way. Generally, the key is to have really good SEO for your sites content so people looking for reviews come first to your content then click your links to buy a product.

This is also a common monetization strategy for YouTubers and other social media influencers.

5. Advertising

There are many ways to do it, but ultimately advertising is a simple concept. You create content that draws people’s attention, then you also show promotional content from brands around, above, below, in front of, in the middle of, and/or after your content so the audience sees it too.

Most ads can be direct sold or programmatic:

- Direct sold ads are ad campaigns the media company’s staff sell directly to brands and agencies; this is expensive because of the sales team required but can result in much higher pricing, especially if the media brand has a deeply engaged audience and/or valuable niche audience.

- Programmatic ads are ads sold automatically on big ad marketplaces. Advertisers are on one side (the “demand side”) looking for opportunities to put one of their ads in front of their target audience, but only if the price if within their budget. Websites with an audience are on the other side (the “supply side”) offering their ad space to be bought. This all happens now on an automated, real-time basis for every ad impression (every individual visit to a webpage) rather than with humans on each side. There are adtech tools for both sides matching advertisers with ad space, creating a market where the more advertisers who want to reach a specific webpage visitor there are, the higher the price they pay for show that ad goes. This is a complicated space with many different approaches and technologies so I will leave it at this for now.

Sponsored content (aka “advertorial”) is high quality content similar to what the media companies normally creates, but it is authored by an advertiser. For example, Goldman Sachs might contribute articles in business news publications that share their analysis of economic trends. Or Walmart might sponsor a cooking-focused YouTuber’s video about how to pick the freshest produce at a grocery store. This content is labeled as sponsored but tends to appear alongside normal content.

Sometimes the advertiser (or their ad agency representing them) already have content they created and want to share across media channels; usually the media company creates the sponsored content for the advertiser, with the advertiser’s input and final approval. Many large media companies that do this, from the New York Times to VICE, created in-house creative agencies that not only handle internal sponsored content but also consult brands (for a fee) on making their marketing content and sponsored content elsewhere better.

Since many media businesses have events (conferences, music concerts, etc.), we can also include event sponsorships here. Major consumer product brands often sponsor the tours of major musicians within certain geographies. Consumer-facing media companies that put on events often earn more money from sponsors than from ticket sales (while events by business media companies are often more like a 50/50 split since they can charge expensive ticket prices).

Product placement is the common practice in video and photo content (including video games) of putting certain products from advertisers in the video or photo as if they naturally belong there. A character in a video may use a certain Samsung phone or drink a Red Bell or drive a Volkswagen, and the brand pays for its product to be included like that. It makes fans of the content feel emotional connection to the brand and desire the product. This sometimes also happens in music, often with a reference to a certain alcohol brand.

These tend to be more complementary ways to integrate advertisers into content and are used my media companies with prestigious brands and deeper audience engagement.

Rewarded ads are common in mobile games but can be used with other types of content as well. You offer your users the opportunity to unlock special benefits (like exclusive content or access to in-game assets like coins or weapons) in exchange for either paying money or watching an advertiser video. These are optional ads that your audience chooses to watch in order to access something. The vast majority of any audience isn’t willing to pay for content so this is a way to monetize those audience members.

Advertising isn’t the focus of this blog, and I’m not a big fan of media companies centering their business model on advertising, so I’ll leave it at that. (Read my post The Problem with Advertising.)

Which is best?

Most successful media companies use more than one of these monetization strategies. Which will be most effective for any given media company depends entirely on the content they want to create, the audience they target, and the ambitions they have for how the company will evolve.

I do believe subscriptions are the heart of a strong media business though. A subscription business model requires you to create high-quality, differentiated content that deeply engages your audience and makes them loyal fans. That means a more financially stable business and more valuable IP. It also puts your company in a stronger position to monetize through most of the other strategies here: advertisers will pay more to be featured to an engaged audience with deeper emotional connection to the content; having loyal fans makes e-commerce viable; your fans trust in your brand means they trust your product recommendations (for affiliate linking).

If you have an equity stake in the business, you should also understand that different business models affect the way investors (and larger companies making acquisitions) value the business. Let’s say a media company has $20m in revenue with $3m in EBITDA and it has been growing 20% year-over-year the last 3 years.

- If all of that revenue is from subscriptions then it is very reliable revenue from loyal fans (who you can easy market new products too) and likely to remain stable for years to come, so investors are willing to pay higher prices for shares in the business. They may value the business at $50m (2.5x revenue, 16.7x EBITDA).

- But if all of that media company’s revenue comes from ads, investors recognize that there is a lot more uncertainty about the future of the business because the advertising market fluctuates dramatically. Maybe then they value the business at $20m (1x revenue, 6.6x EBITDA).

If you founded the company in this example and are now selling it, you would make 2.5x more money if it is subscription-based than if it is ad-based. Also, media companies whose audience is businesspeople (like industry trade publications or podcasts) are generally valued higher than media companies whose audience is everyday people because businesses as customers can afford to pay much more money, tend to be much more loyal, and the advertisers eager to reach them are willing to spend much more money.

—

Originally published on 20 February 2018. Updated on 7 March 2023.