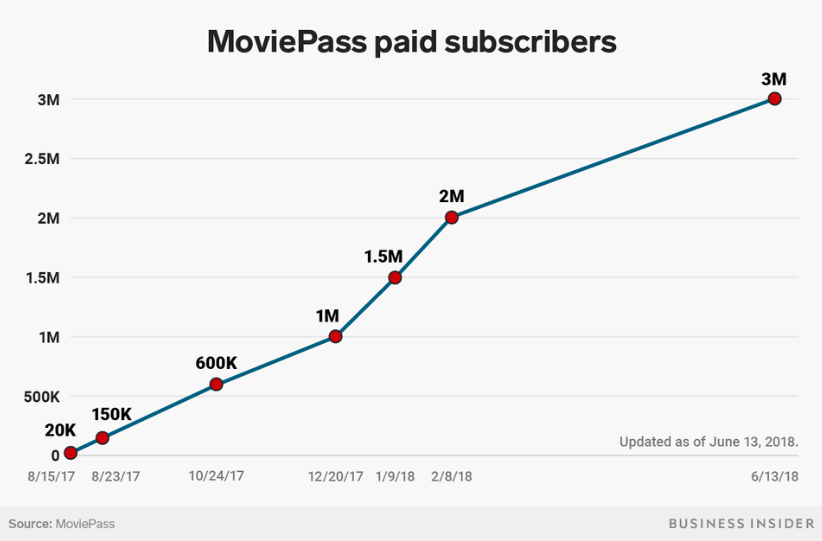

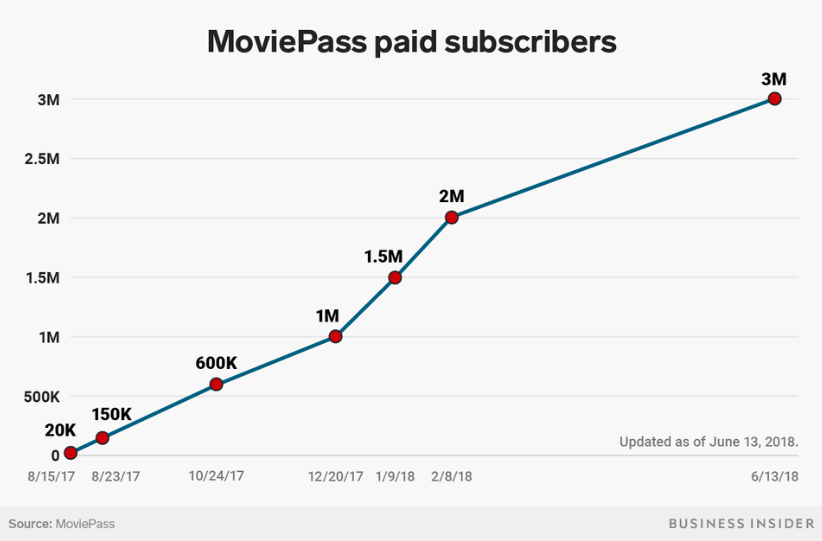

AMC Entertainment announced a $19.95/month subscription last month called the AMC Stubs A-List for movie-goers to see up to 3 movies per week at its theaters (Stubs is their rewards program). This is a big experiment for AMC – the largest exhibitor chain (aka cinema chain) in the world – not least because its CEO Adam Aron has been very critical of MoviePass, which set off a rush of interest in subscription cinema packages after dropping its price from $50/mo to $10/mo last August and growing from 20,000 to over 3M subscribers since.

MoviePass is on a mission to “disrupt” the film industry with an all-you-can-watch membership so cheap it’s a no-brainer for any person to join. The company has negative unit economics (it loses money even from a subscriber going to one film per month) but says it will generate other revenue streams like advertising, selling data to film studios, producing its own films, and convincing exhibitor chains to give it a cut of food & drink revenue (Aron has said AMC would never agree to that).

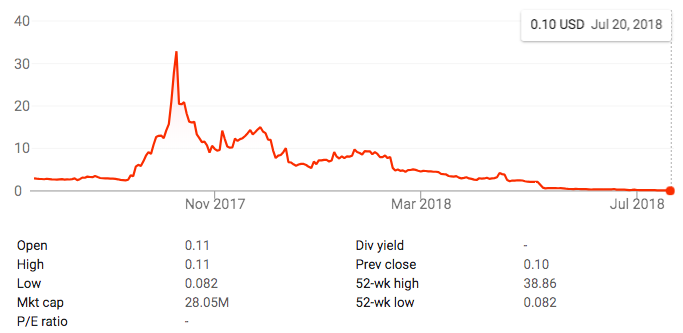

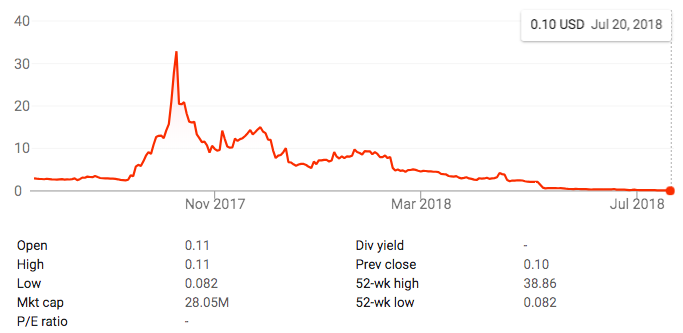

The growth rates of MoviePass led the Nasdaq-traded shares of its holding company, Helios & Matheson Analytics, to increase from $3 a year ago to $38 by October 2017, but the ever-deepening losses have caught up: its shares are currently trading at $0.10 ($26M market cap). Not phased, Helios & Matheson CEO Ted Farnsworth claims they’ll raise another $1.2B in equity and debt financing over the next couple years to expand an in-house film production arm and will be cashflow positive by the end of 2018 (assuming they reach 5M subscribers).

The growth rates of MoviePass led the Nasdaq-traded shares of its holding company, Helios & Matheson Analytics, to increase from $3 a year ago to $38 by October 2017, but the ever-deepening losses have caught up: its shares are currently trading at $0.10 ($26M market cap). Not phased, Helios & Matheson CEO Ted Farnsworth claims they’ll raise another $1.2B in equity and debt financing over the next couple years to expand an in-house film production arm and will be cashflow positive by the end of 2018 (assuming they reach 5M subscribers).

Does a subscription for movie tickets make sense?

A subscription often makes sense when you have a recurring purchase frequency (of roughly the same price point) and when you can offer customers extra benefits for their loyalty that they can’t already get from one-off transactions (like cost savings, improved experience, sense of membership in a community, etc.). The upside for a business is the low cost to acquire a customer (CAC) relative to their lifetime value (LTV) since they keep paying without you having to target them with marketing campaigns every time; predictable financials from a regular payment cycle; and deeper customer engagement (often more spending and more data collected).

We’re several years into “the subscription economy” where it seems companies are testing the idea of a subscription for every product and service consumers use: clothing, cleaning products, wine, dinners, flights, meditation, music, video, books, doctor visits, etc. Nearly every media company seems to be launching a subscription video-on-demand service or subscription membership tier to read articles. Consumers are used to subscriptions for all sorts of things now, and there’s opportunity to bundle them together for joint promotions that acquire new customers (like Spotify x Hulu for $12.99).

To set the context for a movie tickets subscription, let’s consider some stats on the state of movie-going in the US & Canada [1]:

- Three-quarters (76%) of the population over 2 years old went to the movies at least once in 2017 and people who go to the movies tend to go 5 times per year on average. More specifically, 12% of the population goes once per monthly or more, 53% go less than monthly but multiple times per year, 11% go once per year, and 24% go never.

- Half (49%) of ticket revenue comes from those who go monthly or more and most of those (57%) are in the 12-38 year old age range.

- Roughly half of exhibitor chains’ revenue comes from concessions, but concessions have much higher profit margins, so a disproportionate amount of the profit comes from customer spending once they’re in the door.

- Total box office tickets sold was 1.57B in 2002, and has declined in recent years to 1.24B in 2017 (the lowest since 1992). But the sales of those 1.24B tickets amounted to an $11.1B market (the 3rd highest ever after 2016 and 2015). That’s also twice the attendance of theme parks and pro sports events combined.

- Exhibitor chains are increasing ticket prices (2017 avg: $8.97) and concessions prices to make up for the fewer customers and are investing in making the cinema a “premium” experience with leather recliners, high-end food service, alcohol served in-theater, etc. They need to extract more money from the cinephiles who are frequent movie-goers.

A monthly subscription, even at a good price, won’t convert consumers who never go to the cinema or go merely once a year. It could entice a swath of the people who attend movies several times a year to increase their attendance to roughly monthly though…the subscription offers them enough savings and perks when they do go that they decide to try it out, then opt to go to the movies more because they have it (or opt not to cancel it even if they miss a month or two).

Of course, a monthly cinema subscription is most compelling to 2 groups who might see immediate savings: those who already go once per month and those who already go multiple times per month. Monthly attendees already have a habit of going to the cinema as a common activity, so a subscription that gets them in a second time for free will increase the frequency for many of them to above 1x per month (spending more on concessions if not on tickets).

Cinephiles going multiple times to month to the cinema will jump both to save money and to get special perks via a subscription. Of course, these people are the most profitable for AMC and others – already buying lots of tickets and concessions – so dramatically reducing how much they’re paying for tickets could be detrimental to the business.

This is why tiered subscription models make sense if this business model is going to be sustainable. Often when a consumer subscription model is implemented, it starts with just one tier to keep it simple, then adds other tiers over time to capture (and provide) more value to different customer segments. MoviePass and AMC have one-size-fits-all subscriptions at the moment, but the market lends itself to at least a two tiers. The base tier should be a price that entices people to go once or twice a month. This is about expanding the market of monthly customers with a no-brainer price (like <$10/month for 2 tickets) that triggers rapid scale, converting a meaningful percent of those who only go to the movies a few times per year. Perhaps it has restrictions on being used for peak times (i.e. opening night of a Marvel movie) or for IMAX.

The second tier should be for cinephiles; they are fine spending $30+/month at the cinema already, and what they crave is likely special perks and community more than deep discounts on tickets…which is the smart move for the exhibitor too. The goal here is to deepen their engagement further, come up with new offerings for them to spend on, and mobilize them as evangelists. This tier should provide a percentage discount on the third and subsequent tickets per month or be a higher-priced all-you-can-watch offering, include peak times and IMAX movies, have extra concessions and viewing perks, give first dibs on opening night tickets, include online or offline film discussion groups, incentivize bringing friends, etc.

The problem with MoviePass

Let’s consider MoviePass as a marketplace: it has consumers on one side and cinemas on the other, with the consumers choosing which cinemas they want to buy tickets from. Startup marketplaces gain adoption and powerful market position by aggregating consumer demand on one side and sellers (or service providers) on the other. The model thrives in fragmented markets with lots of small- and mid-size companies competing with each other. Because the startup has aggregated lots of consumers on one side, the companies have to participate or risk those customers being directed to competitors. That’s the power marketplaces have over the supply side and exploit to compress supplier margins over time (passing savings on to the consumer while pocketing some as the middleman). MoviePass is aggregating consumer demand through a money-losing ticket subscription then hoping to leverage that to force exhibitors into cutting them into concessions revenue, giving them discounts on tickets, etc. Potentially it will split its offering into multiple tiers, although management has said they’ve no intentions to do that even in the long-term.

The problem here is MoviePass doesn’t actually gain much leverage over exhibitors because this is a fairly concentrated market. There are few mom-and-pop cinemas left in North America (especially few showing major Hollywood films rather than indies). Three companies – AMC Entertainment (owned by China’s Dalian Wanda), Regal (owned by the UK’s Cineworld), and Cinemark – have 50% market share in the US cinema landscape and they’re taking it over more each year (plus they’ve even greater dominance in major metro areas) [2]. In Canada, one chain – Cineplex – owns 78% market share [3]. Each individual consumer only has a tiny number of cinemas that are a convenient travel distance to them that show the major films…and it is probably some combination of AMC, Regal, and Cinemark (or just Cineplex). If a consumer decides they want to go to the movies, they’re most likely going to one of those regardless – MoviePass doesn’t have much power to steer them elsewhere. Movie-going is an offline experience, so having tons of smaller chains around the country collaborating with MoviePass is irrelevant to any given consumer; the only ones that matter are the few cinemas closest to them.

The major exhibitors can provide their own subscriptions that offer more perks to members since they own the show (i.e. they’re vertically integrated): AMC offers 10% off concessions, upgrade to the largest popcorn/drink size, and priority lines for seating and concessions. They can also capture additional offline data on moviegoers like what they’re buying at concessions, who they’re attending with, their mood and appearance (using computer vision), etc. and use all the customer data to improve the in-person experience (ushers welcoming you by name, ordering your usual food/drink in advance with one tap, etc.). Plus, by owning both the online and offline customer interaction, the exhibitors then have the data to sell better targeted advertising that can bridge the online and offline experience.

What will happen to MoviePass?

Ultimately, MoviePass is lacking the financial footing for large lenders or equity investors to back it with the war chest of capital its grand plan would really require. I think MoviePass will continue to burn cash and ultimately get acquired by a major exhibitor (AMC, Cineworld, Cinemark) or SVOD player (Amazon, Netflix) who can make immediate use of its subscriber base and user data.

Unlike most startups where the majority shareholder or board have to compete say over whether to take a deal, MoviePass’ holding co is publicly traded. So if an acquisition offer comes in that is strong based on where the stock has been trading for a while, the company’s leadership opens itself up to shareholder lawsuits if it doesn’t seriously consider it (and have a good reason for turning it down).

This is just the beginning.

The subscription offerings by AMC and other top exhibitor chains can be compelling for all parties if priced and tiered intelligently, and they’ll accelerate further consolidation in the exhibitor market (like SVOD services have triggered in film/TV) because each will want its subscription to contain the popular cinemas in any given city. Consumers will naturally only have one cinema subscription each, so securing their long-term loyalty with one major chain over its rivals will be big a high priority to the exhibitors.

Furthermore, these subscriptions will expand beyond just movie tickets to other offline entertainment offerings. That’s the direction exhibitor chains are already moving in the face of a secular decline in cinema attendance…forward-thinking exhibitor chains are re-envisioning themselves not as movie-watching companies but as what-you-do-on-weekend-nights-with-friends companies. Several chains are incorporating Virtual Reality arcades, others are using some of their theaters for esports tournaments, some have TVOD movie rental if you decide to stay at home, etc. (Cineplex is doing all that and more). By expanding the membership to include activities beyond just movie theaters, they can attract many more of those who only go to the movies a few times per year to sign up. The grand opportunity here, in my opinion, is to create the Amazon Prime membership of offline entertainment experiences…a cost-saving bundle across a wide range of activities that becomes a no-brainer for a large percent of the adult population to enroll in. That’s the direction I expect this is all going in.

Sources:

[1] MPAA THEME report 2017

[2] US market share by screens, from this NYT article

[3] Cineplex market share in Canada from their investor relations